Practical Wisdom: knowing the rules and then breaking them.

Briefly, Practical Wisdom comes from the Greek term Phronesis. In its most basic form, it is defined as the ability to understand a situation, and respond with insightful and effective action.

In a recent and particularly ballsy TED Talk, UC San Diego art and design theorist Benjamin Bratton quite rightly complained that TED is in serious danger of jumping the shark. Bratton’s broadside, calling TED a “middle-brow megachurch [of] infotainment”, accuses the organisation of habitually reducing powerful messages in the name of click bait; oversimplifying extraordinary ideas only to make them palatable to a crowd that can’t/won’t do anything beyond clicking through, sharing, and, at best, parading them around boardrooms, middle-management offices, and next to water coolers in the hopes of looking intelligent or well-referenced.

The danger, he argues, lies in potentially degrading—or worse, disempowering—a forum for genuine genius and even maybe Massive Change Worse, that the ideas posited in the forum (and the way they’re presented) are steadily becoming proportionately watered-down in a ploy to pander to a less interested, less intelligent, lower-common-denomination-dominated audience. Pressing problems giving way to Gladwellean, trite, and all-too-swallowable musings. TED, he accuses, is selling out.

This is very possibly true.

As the quality starts to get lost in the quantity, we need to look to the classic talks that have both relevance and reverence; an impassioned message with a wide and practical application. And plus, this particular cadre of illuminating talks really are great in the board room. Some of them are so good, you can build entire brands on them.

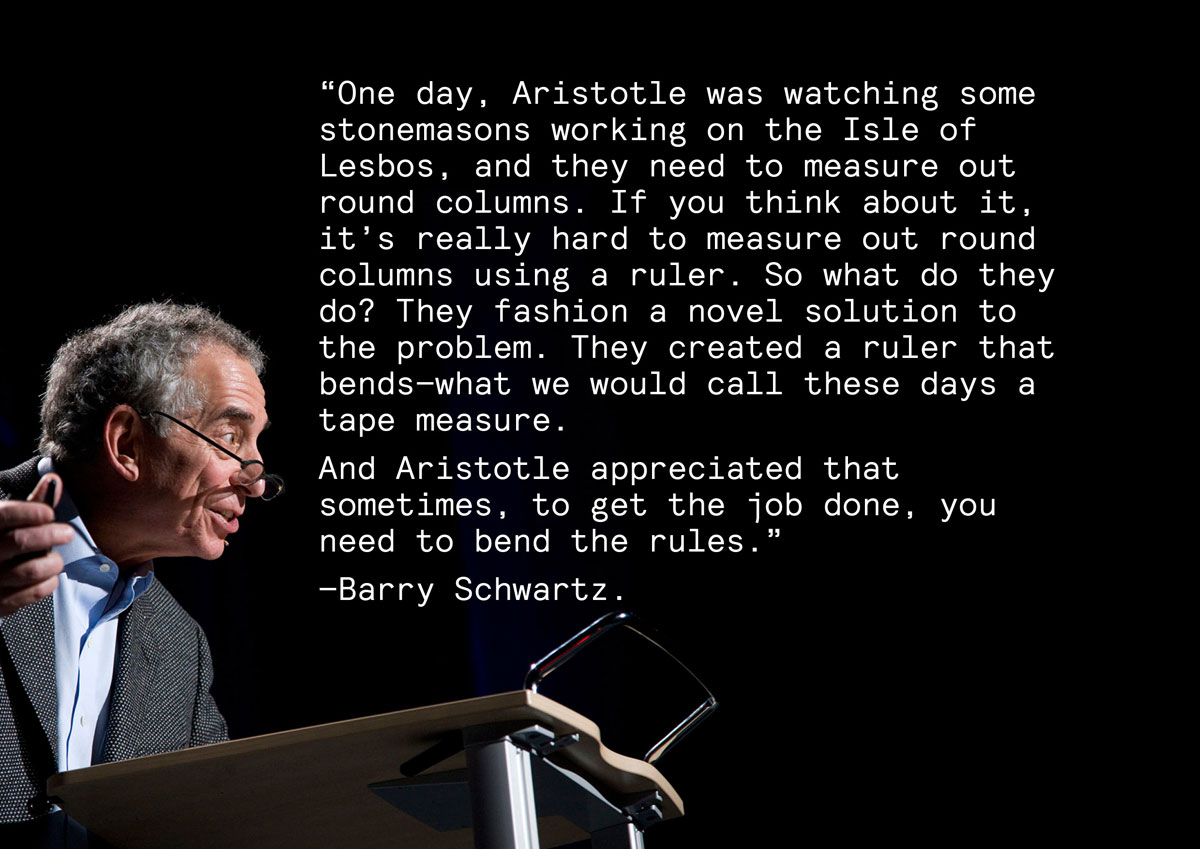

One such talk/idea, is Barry Schwartz’s dissertation on the modern application and relevance of Aristotle’s philosophy of Practical Wisdom.

Briefly, Practical Wisdom comes from the Greek term Phronesis. In its most basic form, it is defined as the ability to understand a situation, and respond with insightful and effective action.

Schwartz quotes directly from Aristotle, “[Practical Wisdom] is the combination of moral will and moral skill … A wise person knows when and how to make the exception to every rule. A wise person knows how to improvise. Real-world problems are often ambiguous and ill-defined and the context is always changing.”

He likens a wise person to a jazz musician – able to recognise the notes on the page but with the ability to ‘dance around them, inventing combinations that are appropriate for the situation and the people at hand.’

Schwartz posits that while rules have their place, and the processes inherent within our environment are necessary, they will not on their own give us the best outcomes. Once we appreciate that every problem is unique, and every challenge different, we stop thinking of rules as paramount in our ability to overcome challenges. We stop absolving ourselves of responsibility once we have the tools to recognise how to solve the issues we face.

But to apply Practical Wisdom requires a thorough, hands-on knowledge of the subject matter. This isn’t recklessness, its an application of learned wisdom. Just as the jazz musician must understand the rules well enough to break them, the wise person must grasp a situation comprehensively, utilise the insight needed to provide effective solutions, and forge new paths and patterns.

This idea of mindful rule breaking is not only the basis of wise and moral everyday decision making; it’s integral to development and progress. In fact, this exact process of understanding the rules, learning the constructs, and then coming up with an unprecedented outcome is the backbone of creativity itself. Just ask one of the most successful brand campaigns of modern times.

In its essence, Practical Wisdom simply champions the importance of thinking for oneself. And, if needs be, outside of the square.

Just as TED’s taught us modern folk a valuable lesson on the virtues of PW, I think it too can benefit from the principle.

Clearly its popularity since going public in 2006 has skyrocketed; from 50 million views in Jan 2009 to more than a billion by November 2013. A savvy brand-building exercise led, no doubt, by a crack marketing team, has truly followed the rules, and as a result, TED is cashing in. But when the message starts to conform to the medium, the purpose can start to get lost. And before we know it, we’re wondering what we were all trying to achieve in the first place. If it’s going to serve as the platform it was originally designed to be, TED needs to look long and hard at its purpose, and its true worth: a forum for ground-breaking, difficult, and revolutionary ideas.

If it needs to operate outside of the mainstream, and not be accessible to everyone, and not be the often clicked-on and too-often misquoted resource of the modern biznizz type, so be it.

As Steve might have said: the world doesn’t need a TED that follows the rules. It needs a TED that won’t respect the status quo. That will push the human race forward.

If it’s really going to change things as it says it wants to, TED needs to stop trying to make everyone happy, and Think Different® once again.